Researcher: Will Valley

Position: Instructor and Academic Director of the Land, Food, and Community Series

Faculty: Land and Food Systems

Problem addressed:

Students in the Faculty of Land and Food Systems have a core set of required courses: the “Land, Food and Community” (LFC) series. Right now, the Faculty is trying to better articulate the theoretical and conceptual frameworks that guide the development of the curriculum in the LFC series, which will allow the evaluation of learning outcomes and approaches to developing future professionals in the food system.

Solution approach:

UBC LFS is currently collaborating with three other universities that are attempting a similar shift in curricula around sustainable food systems education: UC Davis, Montana State University, and the University of Minnesota. Collectively, we were interested in identifying overlapping themes and using an educational framework, signature pedagogy, as an analytical lens to bring coherence to the theories and practices that guide our programs.

Evaluation approach:

The study adopted the signature pedagogy framework to evaluate findings. It uses Shulman’s (2005) definition of signature pedagogy as the “types of teaching that organize the fundamental ways in which future practitioners are educated for their new profession.”

Preliminary findings:

The three themes reported it the literature, systems thinking, interdisciplinarity, and experiential learning, were evident in the faculty’s learning objectives. However, another theme emerged in the analysis of all four programs: collective action.

Can you give some background on the research?

Will Valley: Students in our faculty enroll in programs that span the food system, from nutritional sciences, food science, food market analysis, and dietetics to plant science, soil science, animal science, global resource systems, and food resource economics. What’s unique about our Faculty is [this] diversity, but also that we have a core set of required courses: the “Land, Food and Community” (LFC) series. The core courses are designed to develop systems thinking competencies and interdisciplinary collaboration skills through community-based experiential learning opportunities and collective action projects.

The majority of our students will have careers within the food system (and, like the rest of us, they will all be participants as citizens and consumers), so the health, safety and sustainability of our food system will be fundamental tenets of their work. The decision was made in the late 1990’s that our programs should be intentionally designed to give students exposure to different disciplinary perspectives as they develop into future professionals, and that throughout the degree program, they will collaborate with various social actors within the food system. We involve our students in the community and we invite the community to be present in our courses from first to fourth year. We believe our students need the opportunity to engage with expertise beyond academic ways of knowing to make sense of what’s happening in the real world, to make sense of contextual realities at regional, national and global scales.

Right now, we are trying to better articulate the theoretical and conceptual frameworks that guide the development of our curriculum in the LFC series, which will allow us to evaluate learning outcomes and refine our approach to developing future professionals in the food system.

What was the research question?

WV: We have a paper in review right now. It’s a collaboration with three other universities that are attempting a similar shift in curricula around sustainable food systems education: UC Davis, Montana State University, and the University of Minnesota. Collectively, we were interested in identifying overlapping themes and using an educational framework, signature pedagogy, as an analytical lens to bring coherence to the theories and practices that guide our programs.

There is a small body of literature that discusses the development of these types of programs in North America and Europe. We reviewed this body of literature and looked at the key themes that programs were reporting, which were systems thinking, interdisciplinarity, and experiential learning. We then analyzed the learning objectives of our four programs and asked, were our learning objectives aligning with these key themes in the literature?

What did you find?

WV: The key findings were interesting. The three themes reported it the literature, systems thinking, interdisciplinarity, and experiential learning, were evident in our learning objectives. However, another theme emerged in the analysis of our four programs: collective action. Each program had specific learning objectives that combined the development of personal agency with civic engagement opportunities. Minor themes emerged in the literature and in the analysis of our program objectives, including open-ended inquiry, critical reflection, and seeking balance amongst food-related outcomes. The paper goes into much detail to define these concepts and processes before applying signature pedagogy framework to the analysis of the themes.

How did you evaluate your findings?

WV: We adopted the signature pedagogy framework to evaluate your findings. Shulman (2005) defines signature pedagogy as the “types of teaching that organize the fundamental ways in which future practitioners are educated for their new profession.” The development of new professionals involves a process of staged and multi-level learning that develops capacity to make judgments under conditions of complexity and uncertainty, particularly relevant to the context of food systems which have been increasingly characterized as complex due to their socio-ecological nature. Signature pedagogies “implicitly define what counts as knowledge in a field and how things become known. They define how knowledge is analyzed, criticized, accepted, or discarded. They define the functions of expertise in a field, the locus of authority, and the privileges of rank and standing (Shulman, 2005, p. 54). In Shulman’s framework, signature pedagogies have structure and associated functions at three nested levels. First, the surface structure reflects the visible operational acts of teaching and learning, including the learning contexts and roles of participants in the learning environment. The second level, deep structure, is “a set of assumptions about how best to impart a certain body of knowledge and know-how” that together constitutes essential theories, concepts, and capacities for professional practice (Shulman, 2005). The third level, implicit structure, consists of “a moral dimension that comprises a set of premises and commitments about professional attitudes, values, and dispositions” (Shulman, 2005). This third level is also termed the “hidden curriculum”, i.e., content, process, and behavior of teachers and students during learning activities that constitute, in effect, instruction in professional attitudes, values, and dispositions.

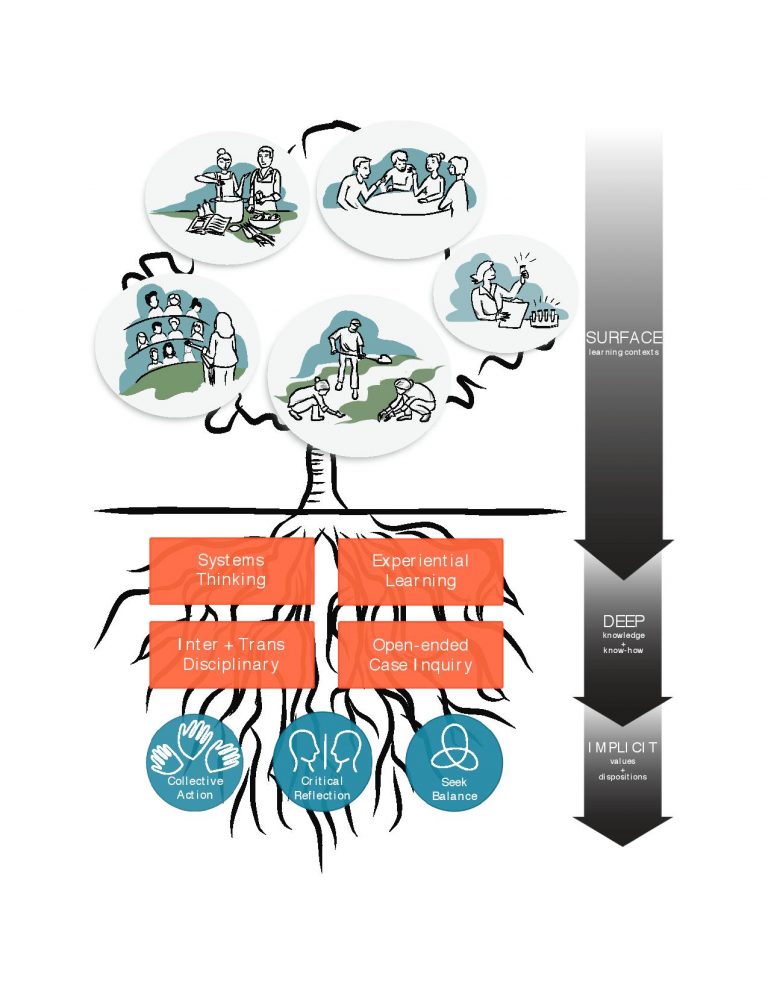

In our diagram, we tried to graphically represent the relationships between themes that emerged in our analysis of the learning outcomes across programs in the four institutions as they relate to the three levels of the signature pedagogy framework. First we described the surface structure. We ask, where are students? And what are they doing? With whom are they working? Our students are in lecture halls, small discussion groups, labs, schools, farms, and community kitchens; they occupy many locations in the food system as well as traditional educational spaces. They are working individually and collaboratively within interdisciplinary groups and they are working with diverse stakeholders beyond the university. Underneath that we look at the deep structure. We have identified to four elements of knowledge and know-how fundamental across our programs: systems thinking, experiential learning, inter- and trans-disciplinary, and open-ended inquiry. Finally, we looked at the implicit structure: what are the values and dispositions we want our students to develop in your programs so that they can embody them as future professionals? For example, critical reflection: we expect our students to be aware of the beliefs and assumptions that exist historically and currently within society around food systems issues. Another is collective action. We want our students to balance the current drive towards individualization in society and consider when systemic issues are best addressed through mobilizing diverse stakeholders towards a common set of goals. The third is seeking balance or optimizing. We ask our students to be wary of any maximizing solutions or silver bullet answers to complex issues in food systems.

How will this study impact teaching?

WV: The responses that we have been receiving from our conference presentations and discussions with colleagues in the field are positive. Our work is helping add clarity to a complex process that has been intuitively built in many different places independent of each other. Many institutions across North America are developing a systems-based, experiential learning, interdisciplinary food [program] but not knowing where to start or how to make the different components related in a coherent way.

We’re at a point now that enough of us are working through these issues and reporting back through scholarly articles, presentations and communities of practice. Now we can begin to target certain aspects of our programs, such as teaching systems thinking or critical reflection competencies, evaluate if we are being effective, and share our results. With a common framework and language, we believe we share and adopt good practices more efficiently across institutions.

How will this study impact future research?

WV: [This research] is already helping us narrow in on certain components of our programs. It’s difficult to evaluate programs as a whole. There are too many components and activities occurring simultaneously to get that fine-grain detail to improve a particular area. We recognize that we are all trying to achieve similar objectives, but we have different approaches, and now we’re coming up with methods to compare our strategies to reach a similar objective or a similar learning outcome.